Endowment

$0

Grantmaking

$0

Gifts Received

$0

Interactive

Graph

Talk to Fred

1914

An Idea Whose Time Had Come

Introduction

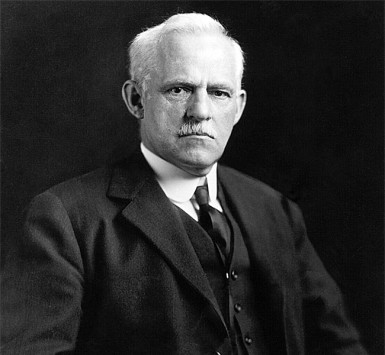

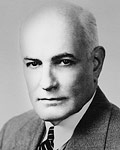

A wise person once said: “How fine it would be,” if an individual who was “about to make a will could go to a permanently established organization…and say, ‘Here is a large sum of money. I want to leave it to be used for the good of the community, but I have no way of knowing what will be the greatest need 50 years from now. Therefore, I place it in your hands to determine what should be done.’” That person was Frederick Harris Goff, lawyer, banker and founder of the Cleveland Foundation.

1914

Belle Sherwin

Social Services Champion on the First Foundation Board

Belle Sherwin (see video) served on the foundation’s board from 1917 until 1924, and she and her sister, Prudence, added substantially to the foundation’s pool of unrestricted monies with testamentary gifts (worth $6.5 million at the time of Belle’s death in 1955) that created the Henry A. Sherwin and Frances M. Sherwin Memorial Fund at the foundation in honor of their parents. But Belle’s informal influence on the foundation’s work was just as significant. Acting in her capacity as president of the Cleveland Welfare Council, it was she who suggested the topic of the foundation’s first municipal survey: “poor relief,” a cause to which she was especially devoted. She also recommended that the foundation hire Raymond Moley as its first full-time director.

After assuming the welfare council’s presidency in April 1914, Miss Sherwin had convened community meetings to discuss the increasing demands being placed on the city’s private and public relief agencies by a severe recession that year. Faced in the fall of 1914 with the imminent prospect of the entire system running out of funds, Sherwin asked the Cleveland Foundation’s survey director Allen Burns, who was a member-at-large of the welfare council, to consider commissioning a study of how to strengthen the city’s relief effort. The foundation’s Survey Committee approved this request, and Burns hired Sherman C. Kingsley, director of the Elizabeth McCormick Memorial Fund of Chicago, and Amelia Sears, welfare director for Cook County, Illinois, to conduct the study.

The “Survey of Cleveland Agencies Which Are Giving Relief to Families in Their Homes” was released on December 1, 1914. It called for the complete reorganization of the City of Cleveland’s relief department. Issued almost 20 years before the New Deal transferred public responsibility for public welfare from the private sector to the state, this recommendation went unheeded. The survey did serve to establish an ongoing working relationship between the Cleveland Foundation and the city’s social coordinators. This bond tightened after Sherman Kingsley became the first executive secretary of the new Welfare Federation of Cleveland, formed in 1917 from the merger of the Welfare Council and the Federation for Charity and Philanthropy.

Most important, the investigation triggered by Belle Sherwin articulated a core challenge that would define the course of philanthropy here and nationally over the next century. “Poverty is a community responsibility,” averred the survey of Cleveland’s fragmented and embryonic welfare system, continuing, “the whole community must realize the extent of destitution, know its causes and remove them….”

1914

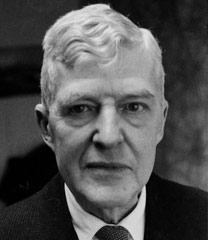

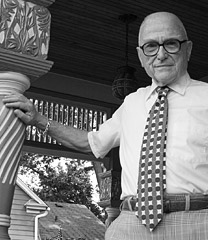

Frederick H. Goff

National Intellectual Treasure

During the first few decades of the 20th century, Frederick Harris Goff was one of Cleveland’s most prominent and beloved citizens. He was also a national intellectual treasure but, sadly, his name is not well known among most 21st-century Americans or even among Clevelanders. This lack of recognition is unfortunate because Goff, like his better-known contemporaries Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, changed philanthropy forever, here and around the world. As the American philosopher William James has stated, “The great use of a life is to spend it for something that outlives it.” As more and more citizens across the globe adopt and adapt Goff’s concept of pooling their charitable assets to create a permanent vehicle for addressing pressing local needs, his humanitarian legacy burns ever brighter. For this reason Goff’s life and career merit reconsideration here.

1914

Goff’s Vision

The World’s First Permanent but Flexible “Community Savings Account”

The Cleveland Foundation was an entirely new concept in philanthropy. Captains of business and industry such as John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie had conceived of creating private foundations to channel their immense wealth into philanthropic activities. Goff envisioned an alternative mechanism for ensuring the honorable and productive use of monies accumulated over and above one’s immediate needs. Endowing such a foundation was a simple and affordable way for individuals of modest to comfortable means to leave a charitable legacy.

1914

James R. Garfield

First Legal Adviser

James Rudolph Garfield, a Columbia University-educated lawyer who began practice in Cleveland in 1888, was the first legal counsel of the Cleveland Foundation. The son of Ohio-born President James A. Garfield, he handled the foundation’s legal affairs until 1946, the year he turned 81. Garfield died in 1950.

During his 32-year tenure as legal counsel, Garfield worked with the probate and trust attorneys whose clients had bequeathed funds to the foundation to make sure that donors’ wishes were clearly understood and scrupulously observed. Untangling knotty issues (often involving misunderstandings on the part of beneficiaries with lifetime interests in the donors’ estates), he was responsible for the smooth and timely transfer of the first $10 million in endowment monies to the foundation.

Garfield’s most shining hour came during heated public debate about the findings of the Cleveland Foundation’s criminal justice survey in 1921. In his damning report about the performance of municipal and county courts, attorney-investigator Reginald Heber Smith documented a host of abuses that conspired to protect Cleveland’s criminals from conviction. Of every 100 felony cases originating with city prosecutors, Smith had discovered, only 29 on average proceeded through to sentencing. Among the causes identified by Smith for the laxity of the system were the defense of habitual criminals by a ring of attorneys with powerful political ties, underpaid prosecutors with inexperienced assistants, and the shirking of jury duty by well-educated citizens.

Members of the judiciary mounted a fierce public counterattack, labeling Smith’s investigation “unjust” and a “criminal waste of money.” Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court judge Homer G. Powell went so far as to threaten to jail the foundation’s board for contempt. The board members promptly huddled with Garfield, who courageously advised his clients to inform “Judge Powell that he could send the sheriff anytime he wanted to receive us.”

1914

Mary Coit Sanford

Donor of the Foundation’s First Bequest

On January 29, 1914, Mary Coit Sanford signed a last will and testament containing a bequest to establish five funds at the Cleveland Foundation. Her confidence in the new community trust, which was less than a month old, undoubtedly stemmed from the fact that Mary knew Fred Goff, if only by his sterling reputation. Mary grew up in Bratenahl, the Cleveland suburb where Goff had once served as mayor.

Descended from one of Cleveland’s founding families, Mary was notably civic-minded. She would help to found the Women’s City Club in 1916 and later chaired the Cleveland branch of the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, a volunteer organization that sought to address local shortages of housing, fuel and food during World War I. Mary’s husband, surgeon Henry L. Sanford, would also participate in the war effort as a member of Cleveland’s famed Lakeside Hospital Unit, the first U.S. Army detachment to arrive in France in 1917.

Mary Coit Sanford died unexpectedly in 1926, less than a year into her tenure as a member of the board of the Cleveland public schools. Twelve years later, after the death of Mary’s husband, the Cleveland Foundation received her bequest of $40,000 (the equivalent of more than $650,000 today), to be divided among five designated funds. The beneficiaries of three of the funds were the Associated Charities, a philanthropic organization that provided direct relief to Cleveland families, and University Hospitals of Cleveland, the successor to Lakeside Hospital. Mary named the Harriet Fairfield Coit Fund and the William Henry Coit Fund in honor of her parents, who had nurtured her aspirations of earning a college degree. These latter funds provided scholarship monies in perpetuity to enable other young women to achieve their dreams by attending the College for Women of Western Reserve University.

1914

The Community Foundation Movement

How Goff’s Idea Has Enriched the World’s Social Capital

Cleveland banker Fred Goff did not rest on his laurels once his idea for a community trust had become a reality. He worked hard to spread the concept as broadly as possible. Even before the Cleveland Foundation was incorporated on January 2, 1914, the publicity department of Goff’s bank sent out a national press release describing the foundation’s structure, purpose and expectations of financial support. Before the month was out, articles announcing the birth of a new kind of philanthropy had appeared in the New York Times, Saturday Evening Post and two progressive journals, Outlook and The Survey. Goff also authored an article about the Cleveland Foundation for the January 1914 issue of Trust Companies magazine.

1915

Groundbreaking Strategy

“To Uncover the Causes of Poverty and Crime and Point Out the Cure”

Fred Goff obeyed the dictum of Cleveland civic architecture designer Daniel Burnham to “make no little plans” as they have “no magic to stir men’s blood.” Less than six weeks after the Cleveland Foundation’s creation, Goff publicly announced that the community trust would undertake as its first act “a great social and economic survey of Cleveland, to uncover the causes of poverty and crime and point out the cure.” The research project, which Goff expected would take two years to complete, would be a way for the foundation, which had no endowment as yet, to make an immediate contribution—by increasing public awareness of the problems facing a community in the throes of rapid urbanization. It would also be an indispensable blueprint to guide grantmaking at that future date when income would be available for distribution.

1915

Landmark Public Education Study

“Nobody else dares do it.”

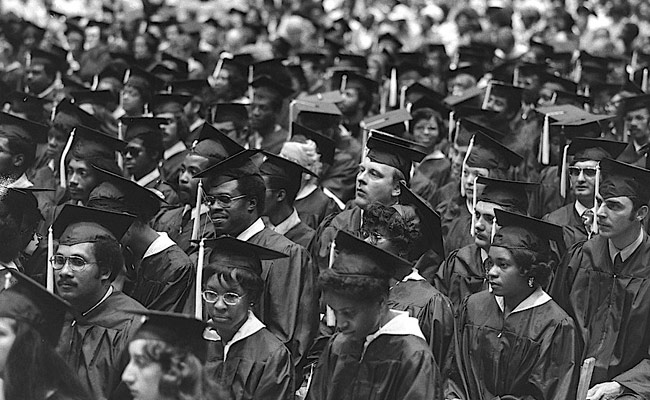

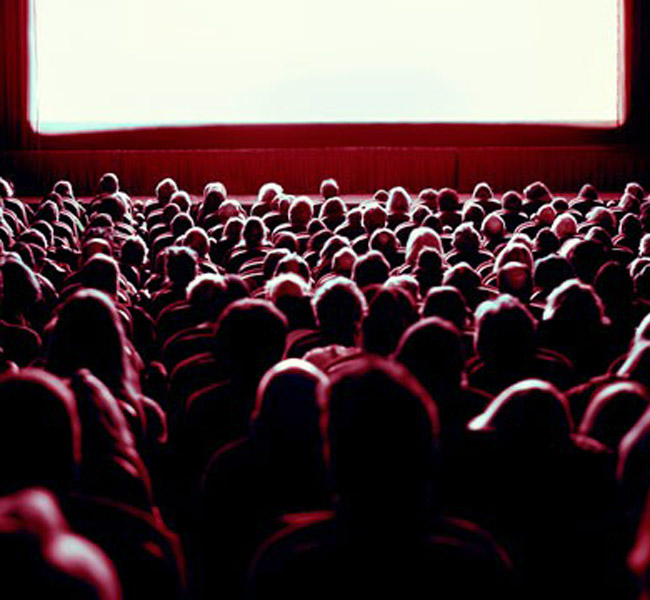

The Cleveland Foundation-commissioned survey of the city’s public schools provided a blueprint for sweeping reforms of an antiquated system unable to meet the educational needs of a flood of immigrant children. Two-thirds of the student population dropped out before the legally permissible age, the survey revealed. Interest in its recommendations for school improvement was intense. Members of the public packed a series of meetings at which overviews of the survey’s 25 reports were presented, and 90,000 copies of individual reports were sold here and internationally to persons concerned about public education reform.

Faced with an overwhelming consensus about the need for dramatic change, the school board hastened to recruit a new superintendent able to implement the survey’s proposals. As of 1923, when the foundation conducted a follow-up assessment of the survey’s impact, 74 of the 100 principal recommendations had been carried out or were in process. (See examples of these reforms.) The results justified the survey’s expense, which had been budgeted at $50,000. More important, the Cleveland Foundation’s qualification to provide bold civic leadership had been demonstrated. As foundation founder Fred Goff had said at the outset, “The schools are the very thing we ought to tackle. Nobody else dares do it.”

1917

James D. Williamson

Board Chairman, 1917–1922

James DeLong Williamson (1849–1935) was the son of Samuel Williamson Jr., a Cleveland lawyer and legislator, and Mary E. Tisdale, a prominent member of the Cleveland Ladies Temperance Union. The family was staunchly Presbyterian (James’s grandfather was a charter member of what would later be known as the Old Stone Church). After graduating from Western Reserve College (A.B., A.M.), Williamson enrolled in Union Theological Seminary and earned his B.D. degree in 1875. That same year he became pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Norwalk, Ohio.

In 1888, Williamson returned with his family to Cleveland, where he pastored Beckwith Memorial Church. He served as acting president (1912–15) and then executive vice president (1915–21, 1924–27) of Society for Savings. In between his terms as VP of the bank, he stepped in as acting president of Western Reserve University.

1919

Launch of the Cleveland Metroparks

The foundation’s call for an expansion in public recreational opportunities led to the first purchases of outlying parkland for what became the beloved “Emerald Necklace.”

The “Emerald Necklace,” as the famed Cleveland Metroparks are known throughout the region and beyond, began to take concrete shape thanks to foundation research. A foundation-commissioned study of Clevelanders’ leisure activities, completed in late 1919, recommended the creation of a council to advocate for the expansion of opportunities to partake of wholesome recreation. The Cleveland Recreational Council immediately began pushing for the passage of a special tax levy to allow Cleveland’s Metropolitan Park Board to make its first purchases of parkland in outlying districts. The levy passed, and the park board set about assembling what has become one of America’s premier park systems.

Today, the Cleveland Metroparks, which recorded more than 16 million recreational visits in 2012, encompasses the Metroparks Zoo and more than 22,000 acres of interconnected green space in 18 reservations. In 2013, the City of Cleveland’s six lakefront parks joined the system, adding an important new strand to the Emerald Necklace. With a startup grant from the foundation, the Metroparks has launched an Urban Beach Ambassadors program, a team of volunteers who will be on hand at Edgewater and Euclid/Villa Angela parks to help improve visitors’ enjoyment of the lakefront.

1919

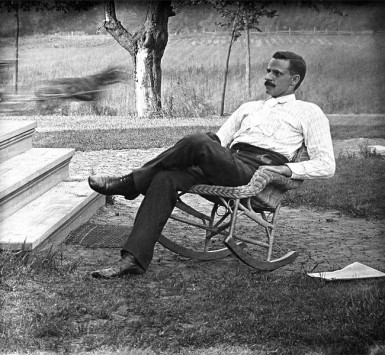

Raymond C. Moley

CEO, 1919–1923

Raymond Moley, best known as a leading member of the “brain trust” that guided Franklin D. Roosevelt into the White House and as FDR’s first assistant secretary of state, became the first full-time director of the Cleveland Foundation on September 1, 1919. Born in the Cuyahoga County town of Berea, Ohio, in 1886, Moley graduated from his hometown college (now Baldwin Wallace University) in 1906 and taught at a country school in nearby Olmsted Falls before being elected “boy mayor” of that rural village in 1908.

He next decided to pursue a master’s degree (Oberlin College, 1913) and managed to earn a Ph.D. in political science from Columbia University in 1918 while teaching that subject at Western Reserve College in Cleveland and organizing citizenship classes for Cleveland’s foreign-born as the mayor’s Americanization chief during World War I. These varied experiences recommended Moley to the board of the Cleveland Foundation, which hired him in May 1919 to complete work on the foundation’s second major municipal survey, a recreation study. When Leonard Ayres (who had conducted the first major survey, on education) declined the offer of the foundation’s directorship, the board turned to Moley, awarding him a contract for a one-year term at a salary of $5,000.

During his four-year tenure as director, Moley shepherded two additional research efforts. The first turned out to be a minor inquiry into the causes of political disaffection among newly arrived immigrants, whose interests Moley continued to champion as the volunteer chair of the Citizens Bureau, a nonprofit organization that offered legal aid to the foreign-born. The dissection of the city’s dysfunctional and unfair criminal justice system, officially requested by the Cleveland Bar Association at Moley’s behest, was perhaps the most important of the eight surveys commissioned by foundation.

In 1922, Moley accepted an offer from Columbia University to become an associate professor of government at its sister Barnard College the following year. His work on behalf of Democrat Al Smith’s failed presidential campaigns in 1924 and 1928 introduced the political science professor to Smith’s successor as New York governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Their formal association began when Governor Roosevelt drafted Moley to design a model state parole plan.

Moley became one of FDR’s most trusted advisers and speechwriters during the governor’s campaign for the Democratic Party nomination for president in 1932. Fred Goff’s former protégé persuaded FDR and the Democrats to embrace a progressive economic and social agenda calling for such reforms as a massive federal public works program to assuage joblessness, Wall Street accountability and transparency, and the separation of commercial and investment banking. The term Moley coined to describe this agenda—the “New Deal”—would forever be associated with Roosevelt’s acuminous first term in the White House.

Moley’s service as assistant secretary of state was brief but consequential. Because his office was located in the West Wing, he acted as gatekeeper of Roosevelt’s time while continuing to draft presidential speeches and fireside chats. A difference of opinion with the secretary of state about foreign trade—Moley favored a certain degree of protectionism—prompted the assistant secretary’s resignation in September 1933. He soon found new bully pulpits as a syndicated political journalist and the editor of the weekly journal Today (which later merged with Newsweek).

When he left the Cleveland Foundation, Moley said that he regretted the move because he considered Cleveland “in many ways the most progressive city in America.” Later in life, he sized up his hometown legacy differently. He now believed that the most important contribution “by far” of the criminal justice survey was “what it did for the Cleveland Foundation.” The high-impact survey, he had come to recognize, “literally underlined the importance of the foundation as one of Cleveland’s great institutions.”

1922

Malcolm L. McBride

Board Chairman, 1922–1941

Malcolm Lee McBride (1878–1941) counted among his ancestors an Irish immigrant who in 1785, after losing a lawsuit to George Washington, was ejected from property owned by the general. McBride’s father was president of the Root & McBride Company, a wholesale dry-goods firm in Cleveland that had become one of the Midwest’s largest such concerns. After graduating from University School, McBride attended Yale (B.A., 1900; honorary M.A., 1920) where he captained the football team in 1899 and served as head coach of the 1900 team. He then joined Root & McBride, becoming vice president and treasurer upon his father’s death in 1909. Elected president in 1929, he held that position for the remainder of his life.

In 1905, McBride married Cleveland-born Lucia McCurdy, and they both played active roles in the city’s public and philanthropic life. She founded the Cleveland Woman Suffrage Party, helped to organize the city’s League of Women Voters, and served on the boards of the Visiting Nurse Association, Cleveland School of Art, and Cleveland Play House, among others. He also served on the boards and committees of various organizations, including the Cleveland Civic League, Cleveland Hospital Council, and Cleveland Association for Criminal Justice. But most notable was his 24-year service to the Cleveland Foundation (1917–41; chair, 1922–41). During his chairmanship the principal value of the foundation’s funds increased from an estimated $359,000 to over $6.7 million, with appropriations totaling more than $2.57 million.

1924

Carlton K. Matson

CEO, 1924–1928

Carlton K. Matson assumed the directorship of the Cleveland Foundation in September 1924, after serving as interim director following the departure of Raymond Moley. Like his predecessor, Matson was a graduate (class of 1915) of Oberlin College. After earning a master’s degree in political science from Columbia University—his thesis examined the State of Ohio’s budget—he worked at New York City’s Bureau of Municipal Research and briefly for a newspaper. He then accepted a position as publicity director of the Welfare Federation of Cleveland and during his time there co-authored a report for the Cleveland Foundation’s recreation survey. Fred Goff subsequently hired Matson to head Cleveland Trust’s public relations department. Matson left Cleveland Trust to pursue a career in financial advertising in Cleveland and Grand Rapids, Michigan. In sum, the foundation’s second director was not “from the conventional uplifter genus,” as Oberlin’s alumni magazine put it shortly after his appointment. “Mr. Matson … has the inquiring mind—almost a restless, unquiet mind,” the magazine went on. “Yet his feet stay on the ground.”

Matson lived up to his advance billing as a realist. At the time of Goff’s death in 1923, the foundation’s endowment was generating less than $15,000 annually in unrestricted income. With its subsidy from Cleveland Trust reduced to $5,000 a year, there was little means to undertake exhaustive, expensive municipal studies. This may not have greatly concerned Matson, who perceived that too many Clevelanders thought that the foundation was a research organization. If the community trust was to fulfill its basic mission of disbursing grants annually for civic benefit, Matson realized that he would have to become actively involved in fund-raising.

In the summer of 1926, he began sending copies of a newspaper article on community trusts to various prominent Clevelanders, a means of introducing himself disguised as a solicitation of their comments. He also systematically sent to every attorney in Cleveland a copy of a speech recently given at the City Club of Cleveland by Ralph Hayes, the director of the New York Community Trust. In the address, Hayes, who had been Goff’s personal assistant at Cleveland Trust, stated his conviction that the invention of the community foundation would one day be ranked as Cleveland’s most important contribution to the world of ideas.

The feedback that Matson received from his mailings betrayed the ignorance, indifference or resistance of the very persons he hoped to convince to endow the foundation or persuade their wealthy clients to do so. Also resulting in disappointment was his attempt to effect a merger of the foundation and the Welfare Federation, whose annual Community Fund campaign consistently generated millions of dollars for its member social service agencies. In the process of pleading the case for the merger, however, Matson converted investment banker Warren S. Hayden, a member of the federation’s executive committee, into a dedicated advocate for the Cleveland Foundation.

Hayden sent a letter to the president of Cleveland Trust in early 1928 that urged the bank to establish a multiple trusteeship as a means of securing a broader base of support for the Cleveland Foundation. Although Hayden spoke solely as a public-spirited citizen, because of his position on the board of the Union Trust Company, Cleveland’s largest bank and, as such, second-ranked Cleveland Trust’s closest competitor, his words carried the promise of the financial community’s cooperation.

Sentiment slowly crystallized among Cleveland Trust officers in favor of multiple trusteeship, but Matson, who had helped to pave the way for this expansion of the foundation’s fund-raising powers, did not witness the Cleveland Foundation’s official affiliation with four additional Cleveland banks in 1931. He had resigned in March 1928 to accept a newspaper editorship. He later directed the Buffalo Foundation for two years.

Matson’s restless intellect eventually brought him back to Cleveland, where he became a greatly admired chief editorial writer for the Cleveland Press. He died in 1948.

1924

Frances Southworth Goff

Kept the Foundation Strong after the Death of Her Husband

Frances Southworth Goff was in every respect the equal of her husband, Frederick Harris Goff. A woman of character and intelligence, she came from a family that helped to settle the portion of northeastern Ohio called the Western Reserve. Her father, William Palmer Southworth, a carpenter who arrived in Cleveland in 1836 and became a builder and small contractor, was credited with laying Cleveland’s first sidewalks and waterlines. After the Civil War, W. P. opened a general store near Public Square, the city’s downtown commons. Frances’s mother, Louisa (née Stark), was active in the suffrage movement and once headed an effort to secure signatures for women’s right to vote.

Sent by her parents to Vassar College (class of 1886), Frances Goff married Fred Goff in 1894, when she was 30 and he was 36. In addition to rearing three children, she fulfilled her role as the wife of a prominent citizen by engaging in good works. Frances was a founder of the Federation for Charity and Philanthropy, organized in January 1913 at the behest of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce to coordinate funding of the city’s social service agencies. The federation had a 30-member board, one-third of whom had been selected by chamber officials to represent the city at large.

Mrs. Goff’s familiarity with the federation’s attempt to provide for public representation may account for her sympathetic response to an observation by a Cleveland Press editorial writer named Livy S. Richard that the Cleveland Trust board was not necessarily the best qualified judge of how to distribute the Cleveland Foundation’s funds. Fred Goff, who had sought feedback on his community trust concept from a wide range of sources, had initially dismissed Richard’s recommendation that money meant for the use of the people should be controlled by the people as “nut radicalism.” But when he showed his wife the letter he had received from the newspaperman, Frances responded, “Fred, I believe that fellow is right.” Goff revised his plan for the foundation’s governance accordingly.

The year after Fred Goff’s death in 1923, Frances Goff was appointed to the Cleveland Foundation board (then called the Foundation Committee) by the mayor of Cleveland, John D. Marshall. Reappointed by Marshall and his two successors, she served on the board for nearly two decades, during which time she responded capably and wholeheartedly to the call to transform her late husband’s dreams and hopes for the usefulness of the Cleveland Foundation into reality. In contemporary terms, you might say she “got it,” writing in 1926 that the role of a community foundation was not just to support “good work being done, but to blaze new highways of progress, to do things in educational, social and civic work which challenge the imagination and arouse the ambition of the community.”

In addition to performing the Foundation Committee’s customary grantmaking duties, to which she is said to have brought a deep understanding of human needs, independence of thought and sound judgment, Goff personally interviewed hundreds of young men and women who applied to the Cleveland Foundation for scholarship aid. She conscientiously helped to draft evaluations of each candidate to be considered by the Foundation Committee.

Frances Goff resigned from the committee in 1942 at the age of 78. She explained that she could not in good conscience serve beyond the time when her usefulness to the foundation was in any way impaired. Leonard P. Ayres, whose tenure on the board overlapped with that of Mrs. Goff, paid a heartfelt tribute to his esteemed colleague, stating, “In the 14 years during which Mrs. Goff and I served together on the Committee, the members were of two classes, and Mrs. Goff constituted the entire first class.”

Goff died on July 12, 1956, having mourned the loss of her daughter, Frances Goff Thoburn, two years earlier. She was survived by son William S. Goff and daughter Freda Goff Waterworth, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

1927

Dorothy Ruth

Assistant to the Foundation’s First Four CEOs

Dorothy Ruth was, for many Clevelanders, the face of the Cleveland Foundation for more than 40 years. A graduate of Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve University, Miss Ruth, as she was respectfully called by generations of grantees, was hired in 1927 as an administrative aide to director Carlton K. Matson. She served in the same capacity under Matson’s three successors and, even after her retirement on December 31, 1967, at age 73, remained an invaluable consultant to the foundation for several years. While on staff, Ruth had a larger scope of responsibilities than her title might have indicated. She reviewed all grant proposals, made follow-up phone calls, sent out grant notification letters and processed each of the hundreds of scholarships given to deserving college students over four decades, personally double-checking that the students received their checks.

In 1972, Dorothy Ruth Graham—she married late in life—established the Dorothy and Helen Ruth Fund at the foundation with a gift of $1,000. In part to honor the memory of her mother, Ruth contributed from $700 to $1,000 saved from her modest pension every year thereafter until her death in 1984. When awarded a cost-of-living increase of $600 in 1983, she contributed that sum as well. The Cleveland Foundation, Ruth explained in a letter, had “better use of it” than she.

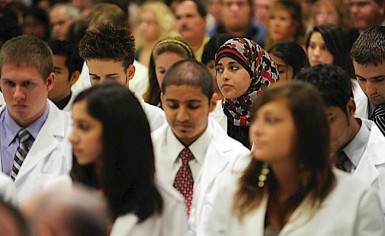

1927

First College Scholarships

Eighteen students received college scholarships ranging from $100 to $725, thanks to the establishment of the first foundation fund designated to provide financial assistance to worthy undergraduates. The Cleveland Foundation presently administers about 140 scholarship funds and has awarded more than $40 million in scholarships in the last 25 years alone (see video).

1928

Leyton E. Carter

CEO, 1928–1953

The Cleveland Foundation board set high leadership expectations for its third director, Leyton E. Carter (see video), recommending that the former political science professor and municipal researcher lend his personal expertise to civic endeavors to a much greater extent than had been the case with his predecessors.

Within a few years of his appointment as director in 1928, Carter had become involved as a trustee or officer with an impressive list of area organizations, including the Adult Education Association, Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, Cleveland Music School Settlement, Cuyahoga County Home Rule Association, Ohio School Survey Commission and the YMCA. He taught at the YMCA’s Cleveland School of Technology, a predecessor of today’s Cleveland State University, for 34 years, staying on to conduct evening courses in government, business and statistics at Fenn College, the result of the Y’s 1930 restructuring of its advanced education program.

In 1931, Carter accepted the call to become grand jury foreman (although his agreement came with the understandable qualifier that he would serve “as long as he could”). He played his most significant leadership role in directing an effort to redevelop Cleveland’s slums that led to the Depression-era construction of the first public housing in America.

Carter’s path to the Cleveland Foundation was similar to that of the foundation’s first director. Like Raymond Moley, who was six years his senior, Carter was born in rural, late 19th-century Cuyahoga County (the Carter family farm in North Royalton was settled by Leyton’s great-grandfather in 1814). He studied at Oberlin College and did graduate work in political science and constitutional law at Columbia University before returning to northeastern Ohio to teach political science at Western Reserve University. Prior to joining the foundation, Carter directed the City of Cleveland’s Municipal Research Bureau. His sudden death in 1953 left the Cleveland Foundation leaderless.

1930

Foster Home Demonstration Project

Seeking to reduce the number of orphaned or abandoned children required to live in institutions on a long-term basis, the foundation initiated a multiple-year demonstration project to be undertaken by two private welfare agencies, the Children’s Bureau and the Cleveland Humane Society, to test the feasibility of placing orphans in foster homes. The demonstration, which proved the benefits of foster family care, gradually reduced the reliance on institutional care here.

1931

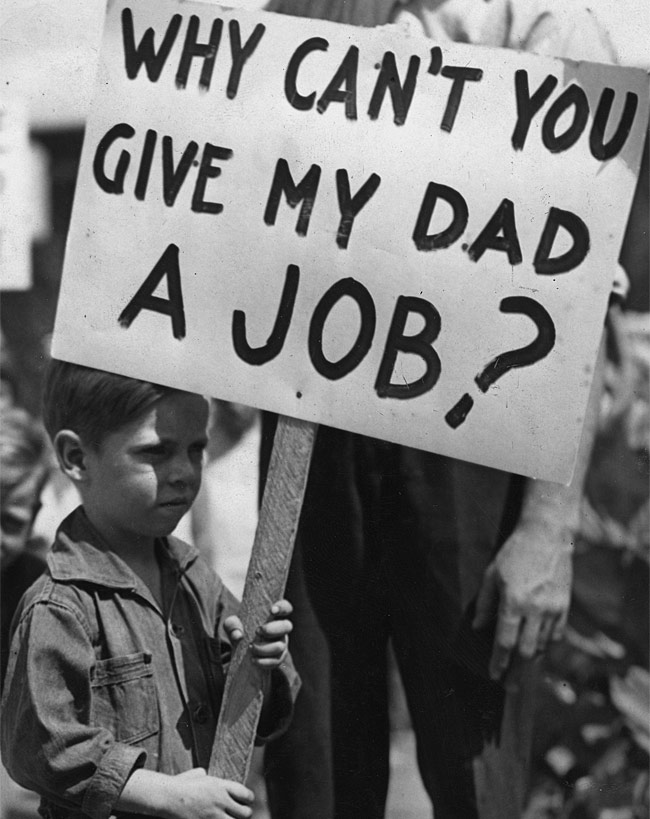

Decisive Response to the Great Depression

Annual emergency allocations from the foundation helped the Welfare Federation meet a desperate need for social services.

Until President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs began, the Welfare Federation of Cleveland (now the Center for Community Solutions) stood as a principal bulwark protecting Clevelanders from the worst dislocations of the Great Depression. In the boom years preceding the stock market crash, the federation had annually raised millions to support the city’s nonprofit welfare organizations and agencies. With more than 100,000 Clevelanders on the breadlines as of 1931, the need for social services of all kinds had never been more urgent, yet it had become painfully clear that the federation would be hard-pressed to meet that year’s Community Fund goal of $5.35 million.

“Don’t worry, Mr. President,” Cleveland industrialist Samuel L. Mather, the father of the community chest concept, told Herbert Hoover when the president had appointed Mather to a committee charged with mobilizing a national relief effort earlier in the year. “Cleveland will take care of its own.”

On the last day of the drive, the fate of the campaign remained uncertain. That evening, 8,000 campaign solicitors gathered downtown in Public Hall to learn the final tally. The audience groaned over the news that an 11th-hour contribution of $150,000 from the estate of Samuel Mather, who had died a few months before, had not pushed the campaign over the top. Then Carl W. Brand took the podium. A Cleveland Foundation trustee, he announced the foundation’s contribution of $75,000, arranged that very day. With the foundation’s timely intervention, the Community Fund surpassed its goal by $30,000, enabling the welfare federation to fully fund its agencies’ increased requests for operating support.

The deepening Depression forced the federation to call again on the Cleveland Foundation the following year to rescue the Community Fund. The foundation continued to make an emergency allocation to the Community Fund every year thereafter until socioeconomic conditions began to stabilize after World War II and private donations once again enabled the welfare federation to take care of Cleveland’s own.

1931

Harry Coulby Funds

Much-Needed Support for Core Grantmaking

A $3 million bequest from Harry Coulby (see video), received in 1931, may have prevented the Cleveland Foundation’s demise during the Great Depression. There is no question that it gave the foundation the means to aggressively promote child welfare.

Having conceived a fascination for the Great Lakes as a boy growing up in Lincolnshire, England, Coulby stowed away to America as a young man of 19. He arrived in New York City in 1884 with experience as a railroad telegrapher under his belt, then made his way to Cleveland on foot, working odd jobs for his meals or a little cash. Finding it impossible to secure a job on a Great Lakes steamship, he became a stenographer for the Lake Shore and Michigan Railroad. An advertisement placed by John Hay, who had served as a private assistant to President Lincoln and U.S. Secretary of State under President McKinley, subsequently caught Coulby’s eye. Hay was looking for a secretarial assistant to help him complete work on a biography of Lincoln, and Coulby fit the bill.

With the 10-volume biography finished in 1886, Coulby accepted an offer from Hay’s brother-in-law, Samuel Mather, to become a clerk at Pickands, Mather & Company, a recently formed Cleveland-based partnership that supplied raw materials to the steel industry. Within a decade, Coulby had assumed command of the company’s fleet of lake freighters and been promoted to the position of partner, assembling a personal fortune in the process.

Upon his death in 1929 at the age of 64, the “Czar of the Great Lakes” left an estate of more than $4 million, the equivalent of about $62 million today. The Cleveland Foundation’s receipt of the bulk of the estate catapulted the foundation into the ranks of the country’s five largest community trusts. More important, it cushioned the foundation from the impact of the Depression, which put several modestly endowed counterparts in other cities out of business.

The Coulby bequest divided his gift equally between two named funds, which have a combined value of more than $90 million today. The first fund was designated for the support of a favored charity of Samuel Mather, Cleveland’s Lakeside Hospital (the predecessor of University Hospitals of Cleveland). The envisioned purposes of the second fund significantly influenced the direction of the foundation’s grantmaking. Perhaps motivated by his own childlessness, Coulby specified that half of the annual income from his gift should benefit “sick, crippled and needy children.” With these broadly restricted dollars, the Cleveland Foundation has commanded the resources to support innovative child welfare programs ever since.

1933

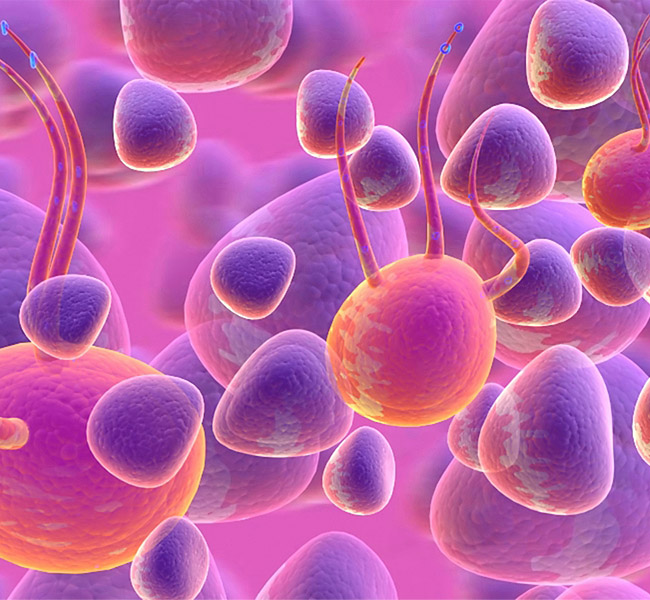

Experimental Polio Research

The foundation made what may be its first medical research grant, awarding $500 to support a City Hospital physician’s study of the causes of poliomyelitis. John A. Toomey, M.D., who was also a professor of clinical pediatrics and contagious diseases at the medical school of Western Reserve University, continued to receive foundation backing through the early 1940s. One of the leaders of the international search for a suspected polio virus, Toomey was unable to confirm in exhaustive clinical trials the hypothesis that polio could be passed from one individual to another. The pre-eminence of his medical practice—he was one of the first physicians in the country to prescribe physical therapy for polio patients—was a contributing factor in City Hospital’s designation by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis as national respiratory care center in the 1950s.

1933

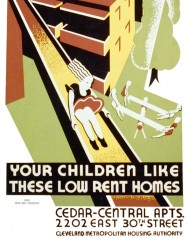

Paving the Way for Public Housing

A master plan to replace 1,000 acres of delapidated housing with low-income garden apartments was prepared by a private redevelopment corporation chaired by the foundation’s director.

None of the many civic responsibilities that Leyton E. Carter shouldered as an expected complement to his position as the Cleveland Foundation’s director proved more significant than his chairmanship of Cleveland Homes, Incorporated. This private housing corporation was formed in 1933 to implement a program of slum clearance and low-cost housing construction to be financed by a $12 million allotment from the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works (PWA).

With blight swallowing up fully one-fourth of Cleveland’s total acreage, Cleveland Homes prepared a master redevelopment plan that called for 1,000 acres of east-side slums to be replaced with new streets and speedways linking low-income garden apartments with stores, schools and other public buildings.

The plan was never fully realized because Cleveland Homes proved unable to raise an additional $2 million required by the federal government. Nevertheless, during his brief tenure as chair of the housing corporation, Carter helped to lay the groundwork for the construction of the first three public housing projects in America. Before PWA decided in early 1934 to assume full responsibility for the first 1,028 units Cleveland Homes had planned to build, the housing corporation had commissioned all the necessary architectural drawings and acquired the land.

Construction of the Cedar Apartments, Outhwaite Homes and Lakeview Terrace was completed in 1937, and three years later PWA placed the public housing complexes under the management of the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA). The founding director of CMHA, former Cleveland councilman Ernest J. Bohn, is usually given sole credit today for the concept of public housing, as it was he who persuaded city council to undertake a catalytic study of blight and influenced state legislation establishing municipal housing authorities. But Carter’s unpaid and time-consuming leadership of Cleveland Homes should also be acknowledged as part of the Cleveland Foundation’s record of accomplishment.

1934

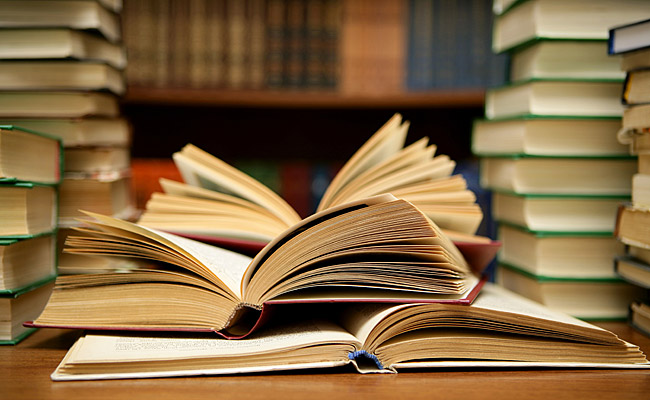

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Focusing Attention on Social Justice and Cultural Diversity

Those who knew Edith Anisfield Wolf (see video), the beloved only child of John and Daniela Anisfield, called her reserved and self-effacing. Yet this unassuming native Clevelander, born in 1889, left a unique mark on the world because of her quiet commitment to social justice. Years ahead of her era in promoting this cause, Edith was influenced by her father, an Austrian immigrant who earned an early fortune in real estate and the garment industry. He put his wealth toward health care for the disadvantaged and improved recreation and education in Cleveland.

In 1901, when Edith was 12, her father welcomed her into his philanthropic work, where she learned to help administer his charitable affairs. Edith studied at Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve University and at the Cleveland School of Art, becoming a published poet. She was one of the first women to be appointed a trustee of the Cleveland Public Library. When she determined to honor her father with a prize, she chose literature—a universally popular vehicle—to bring national attention to the causes they both embraced.

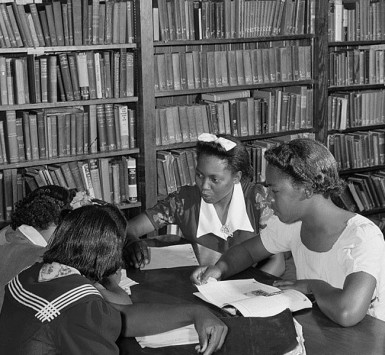

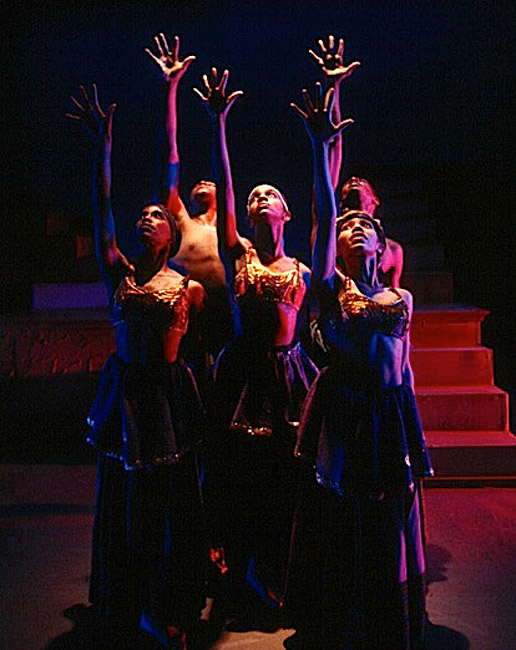

So in 1934, Edith established the Anisfield Prize to honor a scholarly work on race relations. The first prize of $1,000 went to a book published in 1935. Following the 1944 death of her husband, Eugene Everett Wolf, Edith established a second $1,000 prize to honor creative works focused on race and cultural diversity. Today, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards are presented annually to the authors of three or four distinguished books that address racism and foster appreciation of diversity. Since 1996, the awards also have honored a literary artist for a lifetime of achievement.

With each passing year the book awards have grown more prestigious. The jury—presently chaired by scholar, educator, writer and editor Henry Louis Gates Jr.—has worked hard to broaden the scope. In recent years, Edwidge Danticat, Chimananda Nogozi Adichie, Junot Diaz, Mohsin Hamid and Ayaan Hirsi Ali have joined the ranks of such past honorees as Zora Neale Hurston (1943), Langston Hughes (1954), Martin Luther King Jr. (1959), Toni Morrison (1988) and Ralph Ellison (1992).

Originally, the Saturday Review presented the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Edith’s prescient decision to transfer stewardship to the Cleveland Foundation in 1963 ensured the prizes’ continuance. For the foundation, the awards have become an increasingly effective tool for championing racial tolerance, equality and diversity.

1937

The Retreat

Asset Transfer That Carried on the Work of a Shuttered Home for Young Unmarried Mothers

The Retreat, Cleveland’s oldest home for unmarried mothers, faced a difficult decision in 1936. Because parents whose daughters became pregnant out of wedlock were adopting a more tolerant attitude toward the predicament, the need for a residential facility to care for unwed mothers until they gave birth had dramatically declined. The occupancy rate had fallen below 50 percent at the 18-bed Retreat house at 2697 Woodhill Road, prompting The Retreat board’s reluctant decision to close the institution, which had been in operation at various locations since 1868. But what should be done with the organization’s real property and portfolio of stocks and bonds?

Board president Carlotta Creech undoubtedly influenced the transfer of The Retreat’s assets to the Cleveland Foundation. Her husband, Harris, was president of the Cleveland Trust bank and Fred Goff’s successor. In 1937, the foundation received nearly $70,000 from The Retreat, to be invested for the designated purpose of protecting the health and well-being of “unfortunate women and their children.” The Cleveland Foundation was now able to help promote maternal health—the broad cause to which Sarah Elizabeth Fitch, who could rightfully be considered the progenitor of the new endowment fund, was devoted. Coming upon an unwed mother who was about to leap into Lake Erie, Fitch had intervened to prevent the young woman’s suicide and went on to found The Retreat.

1938

Goldblatt’s Early Hypertension Research

A $1,000 grant advanced the highly significant hypertension research of Harry Goldblatt, M.D., director of Western Reserve University’s Institute of Pathology. Goldblatt’s experiments in the 1930s provided a partial answer to clinicians’ bafflement about the causes of hypertension. He demonstrated that if a portion of the main arteries to the kidneys was clamped, blood pressure rose. Goldblatt won international acclaim for his subsequent research identifying elevated levels of renin, an enzyme that regulates arterial blood pressure, as a factor contributing to hypertension.

1938

Model Nursery School

The foundation financed a demonstration project that created a model nursery school at Lakeview Terrace, a public housing project on Cleveland’s near west side. A pioneering early childhood development program, the nursery school was housed in a modern building with well-equipped indoor and outdoor play spaces supervised by an experienced staff. It also offered preschool-age children from tenant families a hot lunch daily and on-site medical services such as immunizations. Hundreds of visitors from other nursery schools and housing projects, social agencies, colleges, hospitals and public health departments came to observe and learn from the school before its operation was taken over by the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority in 1940.

1941

Bellwether Support of African-American Girl Scout Troops

Acknowledging its obligation to confer grants “without discrimination [on the basis] of race, color or creed,” the foundation awarded $1,500 to the Cleveland Girl Scout Council for an expansion of its programming for “negro girls.” The grant, which was used to recruit leadership for new troops and to meet transportation and camping costs for troops requiring financial assistance, was a bellwether of the Cleveland Foundation’s much more substantial support of concerted efforts to serve new racial and ethnic constituencies undertaken by a variety of community organizations beginning in the 1950s.

1941

First Stand-Alone Adoption Service

The foundation supported the start-up and first year’s operation of the Adoption Service Bureau, the first stand-alone agency in the country to assist social service agencies, the courts and prospective parents with the placement of adoptees. Previously, such work was handled as part of a broader portfolio by the Cleveland Humane Society. The bureau’s specialized focus and its advisory board of physicians and lawyers were nationally influential innovations.

1941

Inaugurating Counseling at Divorce Court

The presiding judge of the domestic relations division of the Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court gained the support of the Cleveland Foundation for a demonstration program to slow the rapidly increasing number of divorce petitions. The program showed that provision of the services of a “competent psychiatrist” could bring about the reconciliation of some petitioners, to the benefit of the couple, their children and the community generally. Family counseling and conciliation remain important functions of the domestic relations court to this day.

1941

Innovative Library Program for Shut-ins

Carrying out the wishes of donor Frederick W. Judd, the foundation began to provide annual funds to the Cleveland Public Library (CPL) to enable it to serve those who were too ill, incapacitated or elderly to visit a library branch. CPL, which had been making books available to hospitals, other institutions and the blind with federal support, developed a first-of-its-kind program to deliver materials to shut-ins in their homes. The Judd Fund program is still in operation today.

1941

Katherine Bohm

A Laundress’s Generous Endowment Gift

Katherine Bohm was only 16 when she and her mother emigrated from Germany to the United States around 1872. Following in the footsteps of thousands of other Germans, mother and daughter settled in Cleveland, but the fact that the Bohms were members of the largest group of immigrants in the city gave them no special advantage. They eventually found work as a cook and a laundress in the homes of some of Cleveland’s most prominent industrialists: Fred Beckwith, Ralph King and Samuel Mather.

Fred Goff and Samuel Mather were neighbors, and, as the subject of philanthropy was of immense interest to both men—Mather helped to found the Welfare Federation of Cleveland’s Community Chest fund-raising campaign in 1919—it would have been natural for them to discuss the Cleveland Foundation whenever they visited each other’s homes in Bratenahl, Ohio. Clevelanders could not have been very surprised to learn after Mather’s death in 1931 that he had left a generous bequest to the foundation.

But no one was prepared for the touching news, reported in January 1941 in the city’s morning and afternoon dailies, that Goff’s vision had inspired Katherine Bohm to leave nearly her entire life savings (after providing for a number of distant relatives) to the Cleveland Foundation. During 60 years of unremitting toil—later in life she had cleaned offices in downtown Cleveland and washed laundry in her three rented rooms—she had accumulated well over $10,000. Prudently invested in blue-chip stocks, Bohm’s nest egg would be worth more than $150,000 today.

Bohm had been almost completely blind as a result of inoperable cataracts when she died, just a few days before her 80th birthday, in 1936. She had lost a leg to diabetes, but had retained her independent spirit. The gift of $6,500 that established the Katherine Bohm Fund was free of any restrictions; income from the fund was to be used, at the foundation’s discretion, to improve the quality of life in her adopted community. Fittingly, the first grant of Bohm Fund monies was awarded to the Cleveland Society for the Blind to pay for clients’ eyeglasses and prosthetic eyes.

1942

Carl W. Brand

Board Chairman, 1942

Carl Widlar Brand (1880–1942), educated in Cleveland’s public schools, was a resourceful young man. To earn money to attend Spencerian Business College, he organized a retail coffee route and made deliveries via bicycle, clerked at a soda-water fountain, collected bills for a plumber, sold scorecards at baseball games, and worked as a doorboy at the Roadside Club, an establishment frequented by patrons of the nearby Glenville Race Track. After graduating from business school he went to work as a clerk for a railway company and studied law at night.

In 1898, Brand was earning $25 a week as manager of the Hoffman Hinge Company when his maternal uncle, Francis Widlar, asked him to join his coffee and spice packing business as a billing clerk at $12 a week. Despite the hefty pay cut, Brand sensed an opportunity and worked his way to the position of manager. In 1910, after his uncle’s death, he became president of the Widlar Company. At the 1920 convention of the National Coffee Roasters Association he was elected to a third consecutive term as that organization’s president. Brand’s commitment to civic pursuits was equally energetic. He served as president of the Children’s Fresh Air Camp and Hospital, director of the Cleveland Community Fund, and trustee of the Welfare Federation.

1942

Fred S. McConnell

Board Chairman, 1942–1955

After graduating from Oberlin College in 1899, Fred S. McConnell (1876–1959) entered his father’s wool business in Mount Vernon, Ohio, and the following year married Grace Jenner. He succeeded to the presidency of the J. S. McConnell Wool Company upon his father’s death, but several years later decided to enter a different field: coal. In 1910, he became head of the Eastern Kentucky Coal Company, leaving seven years later for Cleveland at the behest of George Enos, founder and president of the Enos Coal Mining Company, which operated mines in Indiana. McConnell became president of Enos Coal after its founder’s death in 1940. He would also serve as president of the National Coal Association (1943–46) and the Bituminous Coal Institute (1943–51).

Grace had died in 1938, and in 1943 McConnell married the widowed Ann Bomberger Balkwill. She served on the St. Luke’s Hospital Women’s Board and on the senior board of Amasa Stone House. In addition to McConnell’s long service with the Cleveland Foundation, he was president of Karamu House during its early years and an elder of the Church of the Covenant.

1942

Lynn J. and Eva D. Hammond

Donors of the First Funds to Help the Aging

The first funds received by the Cleveland Foundation in the field of aging came from the nearly $1 million estate of Lynn J. and Eva D. Hammond in 1942. Lynn Hammond, who was predeceased by his wife, stipulated that the income from their estate should ultimately fund modest pensions for elderly men and women selected by the foundation as “worthy and deserving.” The monies were to be used first to provide annuities for 33 of the couple’s distant relatives, friends, servants and, most significantly, the retirees of Strong, Carlisle & Hammond, a maker of machine tools and steel mill supplies that Hammond had helped to build into a successful enterprise. Before the principal was transferred to the Cleveland Foundation, the estate also had to fulfill bequests of $5,000 to a number of charitable organizations, including the Masonic Home in Springfield, Ohio.

The source of the Hammonds’ concern for the dignity and comfort of the elderly is not precisely clear, but hints may be found in Lynn’s life story. Born in Cleveland in 1864, he was orphaned around the age of 10 upon the untimely death of his father, Horace, a paymaster at the Cleveland Rolling Mills. An uncle took the boy in. As a young man, Hammond clerked at the rolling mill before hiring on as a bookkeeper and the first employee of the predecessor firm to Strong, Carlisle & Hammond. At his death in 1940, Hammond was the company’s chairman. Did his appreciation of the misfortune that can befall even the meritorious and his gratitude for the hard work of his employees contribute to his keen desire to help seniors who had lived productive lives, but due to socioeconomic realities or unforeseen calamity had found themselves in need?

Whatever the motivation for its creation, the Lynn J. and Eva D. Hammond Memorial Fund helped to propel the Cleveland Foundation into the field of aging, where it would assemble a nationally recognized record of supporting innovation and excellence. (Click on the following links to learn more about model geriatric programs launched with foundation support, such as the Golden Age Centers, Judson Park and the Successful Aging Initiative.)

1951

A. E. Convers Fund

Endowment Monies with Infinite Flexibility

Albert E. Convers was the chairman of Dow Chemical Company and one of the company’s largest shareholders at the time of his death in 1935. The Massachusetts native had formed a lasting attachment to Cleveland, however, during the 30 years he operated a tack manufacturing company here. Believing that the community in which he laid the foundation for his fortune should share in his wealth, he bequeathed almost $4 million to the Cleveland Foundation—with no strings attached.

This was the largest gift received to that point for unrestricted purposes. Demonstrating rare humility in addition to admirable generosity, Convers wanted to provide the community with the means in perpetuity to launch important projects and address critical problems that he himself could never have imagined.

Ever since the first income from the A. E. Convers Fund was realized in 1951, it has generated millions of dollars for grants and supported projects in virtually every program area. Today, the Convers Fund is valued at more than $171 million. The fund’s annual income represents fully 20 percent of the foundation’s unrestricted dollars, allowing flexibility to meet the changing needs of Greater Cleveland.

1953

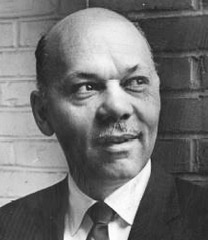

J. Kimball Johnson

CEO, 1953–1967

Chicago native J. Kimball Johnson enjoyed a pioneering career as the top Cleveland administrator for the federal government’s alphabet soup of new social service agencies before becoming the fourth director of the Cleveland Foundation. Having ultimately been transferred from Cleveland to the Chicago regional office of the newly created U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Johnson had sought the foundation’s directorship after Leyton Carter’s sudden death in 1953 in the hope of returning to his adopted city.

Johnson (known as Kim to his friends) had moved to Cleveland in 1911 at age 10. After graduating from Lakewood High School, he earned a bachelor’s degree in metallurgy at the Case School of Applied Science, followed by a master’s degree in civil engineering. His work as a civil engineer for a private contractor specializing in sanitary engineering projects eventually took him to Cuba, where he supervised the construction of a $5 million waterworks and treatment system for a Havana suburb.

Returning to Cleveland at the dawn of the Depression and faced with unemployment, he accepted a job as a caseworker, visiting needy families to determine if they qualified for direct relief from Cleveland’s Associated Charities. This social work experience, teamed with his civil engineering background, made him an obvious choice to help Cuyahoga County’s relief director launch a new federal employment program in 1933. The county’s Civil Works Administration would put 42,000 Clevelanders back to work, and Johnson’s managerial skills attracted attention in Washington, D.C. In 1937, he was recruited to become a field office manager for the Social Security Administration. During World War II, he served as regional chief of field operations for the country’s manpower mobilization effort. After the war, he was tapped to head a five-state regional office that administered all of the programs then operating under the auspices the Social Security Administration, including the Food and Drug Administration and the Office of Vocational Training.

The Cleveland Foundation recorded its greatest growth to date during the first decade of Johnson’s tenure as director. Between 1953 and 1963 the foundation’s endowment swelled from about $18 million to $65 million, an increase of more than 250 percent. Johnson had only his stalwart assistant, Dorothy Ruth, and a stenographer to help him process upward of 250 grants totaling in excess of $2 million annually. Buried under an ever-expanding mound of paperwork, he came to question the increasingly standardized nature of the foundation’s decision making about how best to distribute its undesignated income. With his extensive social service background, he grasped that the changing dimensions of the socioeconomic problems facing Cleveland required exceedingly innovative solutions.

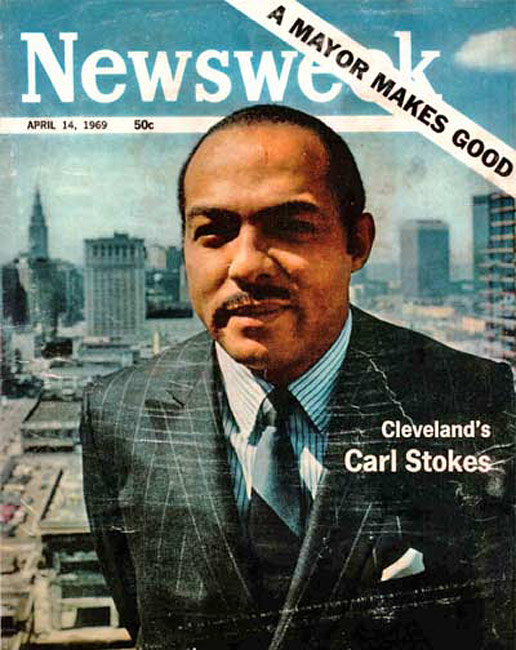

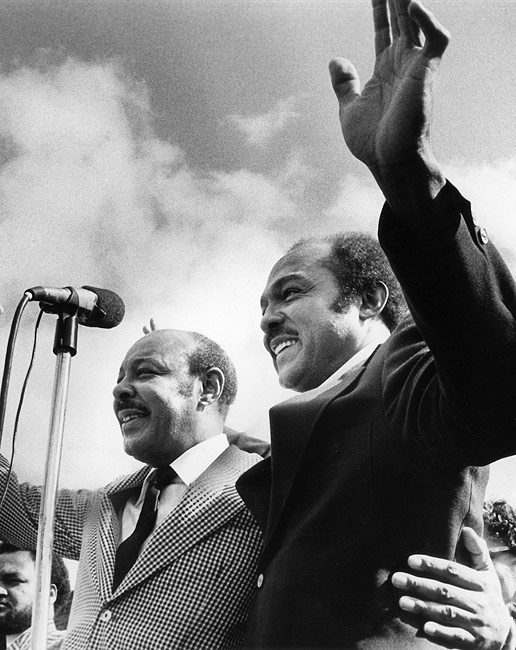

Between 1953 and 1961, Cuyahoga County had lost a staggering 65,000 manufacturing jobs, and the hardest hit were those with the least seniority: African Americans, originally from the South, who had come north seeking factory jobs during and after each of the world wars. Cleveland’s welfare costs had skyrocketed 500 percent over the course of the 1950s, as the children of the idled workers themselves began to drift onto the relief rolls. As of 1961, two-thirds of the out-of-school youth between the ages of 16 and 21 living in the central city were unemployed. In the east-side neighborhood of Hough, the percent of unemployed youth stood at 79 percent.

Acting on Johnson’s recommendations, the Cleveland Foundation poured $400,000 on a project-by-project basis into programs for the residents of Hough alone between 1953 and 1961. Also to his credit, he recognized the need for new, coordinated approaches to solving the multitudinous and interrelated problems of the central city. Johnson regretted that the foundation’s astounding growth, although gratifying, gave him little time to think and act other than mechanically. He retired in 1967, the year after Hough erupted in violence, becoming a symbol, known around the world, for the anger of African Americans toward the inequities of opportunity their country afforded them. He graciously stepped down to allow a younger leader with a demonstrated record of success in fighting prejudice and inequality take the Cleveland Foundation in a bold new direction.

1954

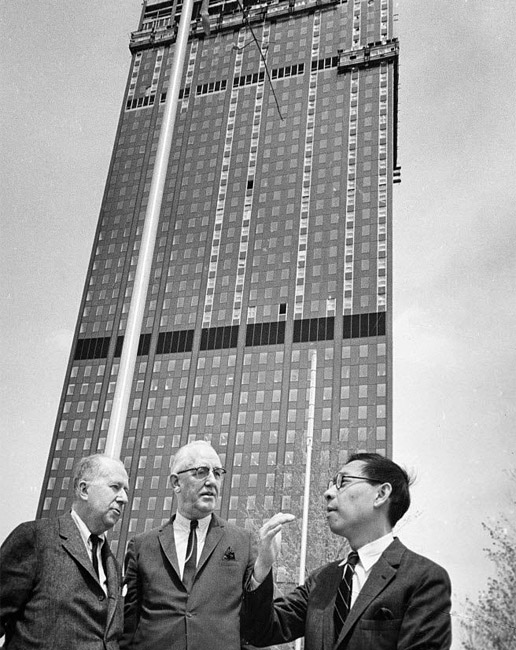

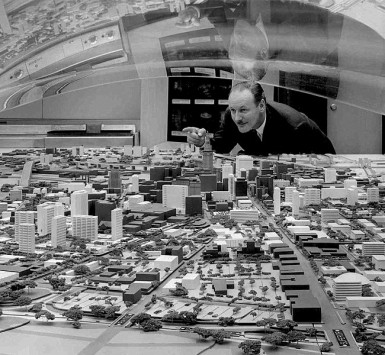

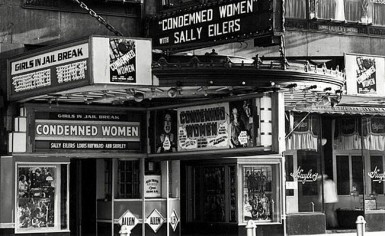

Downtown Cleveland’s Resurgence

Starting with the Erieview urban renewal project of the 1960s, the foundation has been a steadfast supporter of initiatives to reverse postwar stagnation in the city’s core.

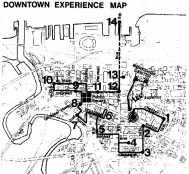

In 2013, Forbes ranked Cleveland as one of 15 cities with a resurgent downtown. The magazine’s appraisal was based on information provided by the Downtown Cleveland Alliance, the latest in a long series of endeavors undertaken with the support of the Cleveland Foundation to reverse the postwar stagnation of Cleveland’s core.

Today, the central city can boast of several impressive measures of good health, starting with the $1.7 billion invested within last decade in new downtown development. Millions more will be invested in proposed hotels, apartments, parks, landscaping and public art and even a full-service grocery. The nation’s eighth largest downtown workforce—nearly 150,000 people strong—pours into the central city each weekday. Roughly 10,000 people live downtown, and almost 16 million people patronize downtown events and attractions each year.

Many visitors might find it hard to believe that, not too long ago, downtown Cleveland emptied out after dark, and blight had overtaken entire quadrants of the city center.

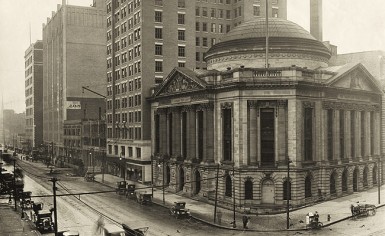

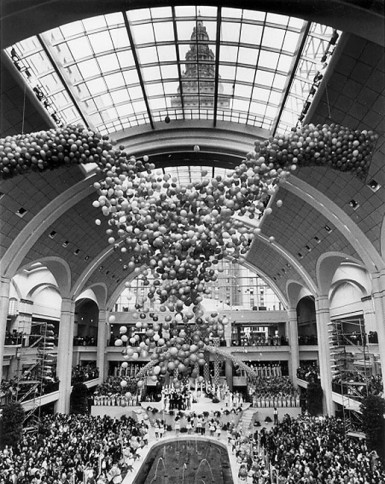

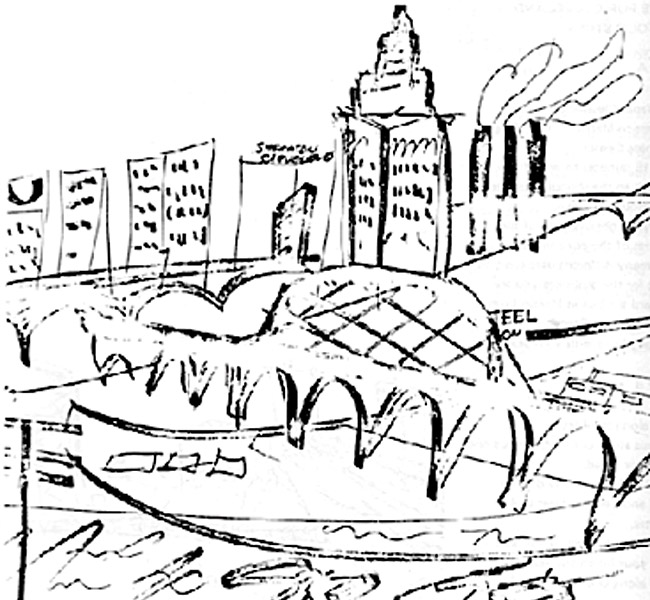

Downtown renewal had stalled during the Depression and never recovered. As of the 1950s, only one or two major new office buildings had been built since the Terminal Tower went up on Public Square in 1929. The pressing need for urban renewal resulted in the creation in 1954 of the Cleveland Development Foundation (CDF), a nonprofit corporation that raised $2 million from the corporate community to invest in redevelopment projects. Supported with early-stage operating grants from the Cleveland Foundation and the Leonard C. Hanna Jr. estate, CDF focused first on building low-income housing, so that slum land could be cleared in preparation for redevelopment.

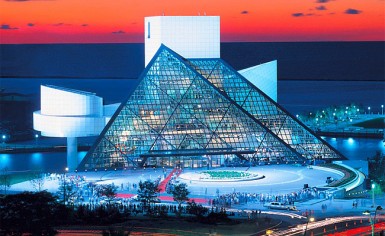

Then, in 1960, CDF unveiled a $500 million citywide master redevelopment plan underwritten in part by the foundation. The plan, which was formally adopted by the City of Cleveland, included a massive downtown renewal project called Erieview. Conceived by internationally known architects I. M. Pei & Associates, Erieview envisioned $100 million in new construction, including government, office and apartment buildings, retail spaces and even a hotel, for a blighted area immediately northeast of downtown overlooking the lake.

Except for the hotel, the downtown plan had been implemented by the mid-1970s, and Erieview’s scale influenced future redevelopment efforts, which focused on a series of big-time projects: indoor shopping malls, museums, stadiums, a convention center and a medical technology showplace. The Cleveland Foundation supported many of these endeavors, typically by providing planning, site analysis or design grants or supplementing construction budgets with funding for public amenities. The foundation also facilitated improvements in downtown infrastructure and downtown transportation, providing planning grants for a county-wide Regional Transit Authority in the 1970s and the Euclid Avenue Dual Hub Corridor, the predecessor of the HealthLine, in the 1980s and ’90s.

In the late 1990s, civic attention turned to the still-decaying sections of downtown lying beyond or in between the bustling big-development clusters. A new nonprofit economic development corporation called the Downtown Cleveland Partnership (DCP), comprised of a cross-section of downtown business interests, had recently been established, and the Cleveland Foundation provided a $250,000 grant that allowed DCP to study the feasibility of innovative redevelopment projects that might not otherwise be considered by small property owners. In 2001, the foundation contributed $1 million to establish a second catalytic fund at DCP. Providing low-interest loans to property owners willing to undertake exterior renovations, the fund particularly aimed to improve the rundown appearance of lower Euclid Avenue.

Seeking a steady and significant source of funding for its economic development activities, the Downtown Cleveland Partnership began to push in 2005 for a special tax assessment called a business improvement district (BID). Property owners controlling 60 percent of downtown’s sidewalk frontage had to approve the BID’s establishment, as they would be assessed additional taxes to pay for improved maintenance, safety and marketing services. Actively championed by the Cleveland and George Gund Foundations, the BID went into effect in 2006, raising a first-year budget of $3 million for the Downtown Cleveland Partnership’s successor organization, the Downtown Cleveland Alliance. A $450,000 grant awarded by the Cleveland Foundation in 2008 further strengthened the alliance’s work to make downtown more welcoming for visitors, new and existing residents, and business development.

1954

Innovative Senior Services

Before the foundation provided start-up funds to the Golden Age Centers of Cleveland (GAC), few if any local social service programs specifically addressed the needs of senior citizens. GAC’s first project—a recreational center for tenants 60 and older at the Cedar-Central public housing complex—was a popular success. The innovative organization went on to open 15 additional centers offering a wide spectrum of services to the elderly.

1955

John L. McChord

Board Chairman, 1955–1956

Born in Lebanon, Kentucky, John Lisle McChord (1897–1956) graduated from Washington & Lee University (1918) and Harvard Law School (1922), serving in the military during World War I. He worked in the legal department of the Cleveland Automobile Club before joining the firm of Calfee, Fogg & White as a partner in 1927. For many years he was a member of the probate and trust committee of the Ohio State Bar Association, and in 1949–50 served as president of the Cleveland Bar Association. He was a director of Union Savings & Loan, vice president of the Family Service Association of Cleveland, and trustee of the Welfare Federation of Greater Cleveland. At age 58, he succumbed to a heart attack.

1956

Ellwood H. Fisher

Board Chairman, 1956–1962

In the late 19th century, Manning Fisher worked for a grocer who owned 150 stores throughout New York City. Inspired by his boss’s success, in 1907 Fisher set out for Cleveland and opened his first grocery store on Lorain Avenue. His brother Charles soon joined him, and by 1916 the Fisher Brothers Company had 48 stores operating under the cash-and-carry system. Manning’s Dartmouth-educated son, Elwood Huff Fisher (1899–1975), would enter the family business as an assistant buyer.

By the time of his father’s death in 1931, Elwood Fisher had assumed the presidency of the supermarket chain. When the company celebrated its 40th anniversary in 1947, it was operating 211 stores. Fisher had married Marion Shupe, who served on the boards of Amasa Stone House, the YWCA and Camp Ho Mita Koda. He helped to found Bluecoats Inc., which provides aid to families of police and firefighters killed in the line of duty. He was also on the board of the Cleveland Zoological Society and was the first chairman of Fenn College, predecessor of Cleveland State University.

1956

Information Services for Cleveland-Hopkins Air Travelers

With increasing numbers of persons traveling by air, the Cleveland Foundation supported the plans of the Travelers Aid Society to expand its services to Cleveland-Hopkins Airport. Backed by a two-year grant, the society set up an office at the airport to provide information, assistance or crisis intervention to the traveling public.

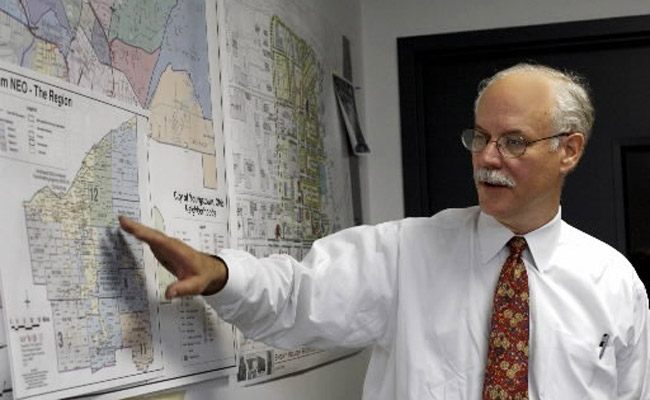

1957

Early Study of Metropolitan Government

The Metropolitan Study Commission (METRO)—an investigation of the advisability of converting Greater Cleveland to a metropolitan form of government—got under way with the help of Cleveland and Ford foundation grants. METRO's findings about the benefits of consolidation failed to convince voters when the issue came to the ballot in 1958, but study director James A. Norton went on to become the fifth director of the Cleveland Foundation.

1957

Poison Information Center

Recognizing the dangers posed by the thousands of new household products coming into routine use, the Academy of Medicine of Cleveland established a Poison Information Center with a start-up grant from the foundation. The center offered physicians detailed information about the chemical composition of all types of toxic substances and first aid advice to members of the public who called in seeking help in treating cases of accidental poisoning.

1958

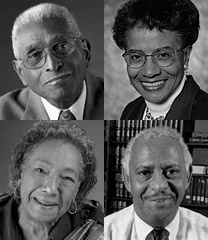

Emergency Aid to African-American-Run Hospital

Forest City Hospital, a 100-bed general medical center built by a group of African-American physicians who wanted to practice in a hospital free of race restrictions, survived its difficult first year of operation with the help of the foundation’s $35,000 emergency grant. Its financial footing regained, Forest City served the residents of Cleveland’s far east side for 20 years. When the hospital closed, its assets were transferred to the new Forest City Hospital Fund at the Cleveland Foundation. In 1981, fund monies helped to launch a capital campaign to replace the antiquated mansion housing the Eliza Bryant Center for the frail elderly in Hough with a new $4.5 million facility that doubled the nursing home’s capacity.

1960

1960 Annual Report

1960

Attempt to Address Desperate Conditions in Hough

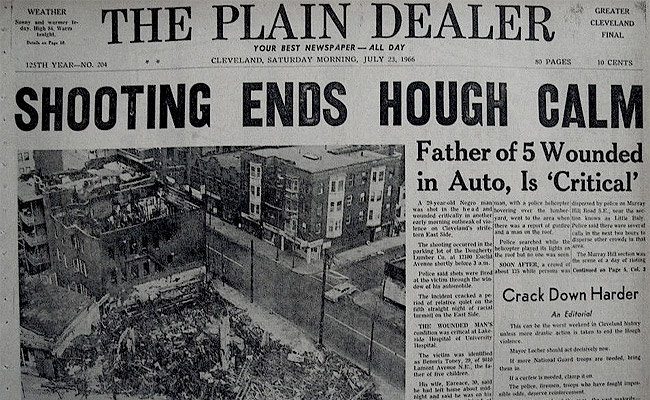

Between 1950 and 1960, the once-fashionable residential area on Cleveland’s east side known as Hough underwent a rapid demographic transformation, changing from 95 percent white to 74 percent African American. No longer a middle-class enclave, Hough suffered from rising unemployment, unacceptable poverty rates, a high incidence of crime and delinquency, and the decay and overcrowding of its housing stock.

In the 1960s, the Cleveland Foundation contributed $106,000 over five years to the Welfare Federation of Cleveland to support the development of a comprehensive social services plan to ameliorate the problems besetting the 80,000 residents of this two-square-mile central-city neighborhood. Living conditions still festered in Hough five years later, but the endeavor was a prescient attempt to address an impending social crisis that erupted into the full-blown Hough riots of 1966.

1960

Legal Representation for Indigent Defendants

The public defender’s office of Cleveland’s Legal Aid Society was established with a $100,000 grant two years before the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that state courts must provide counsel to represent indigent defendants in criminal cases.

1960

Promoting Fair Housing and Integration

The foundation displayed considerable courage in supporting a variety of programs aimed at overturning entrenched patterns of segregation.

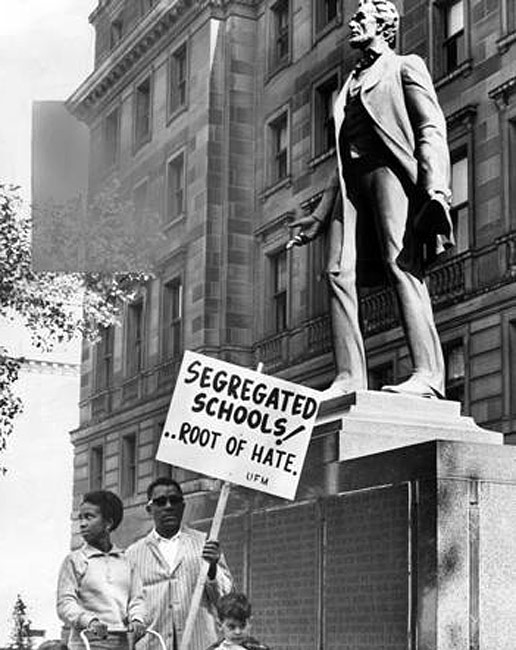

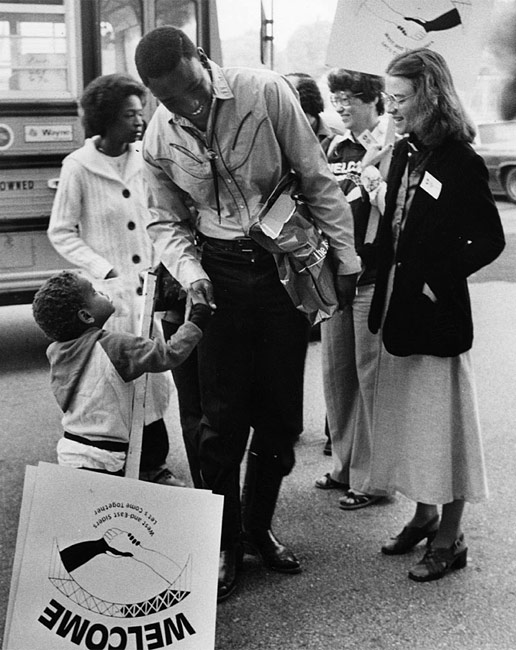

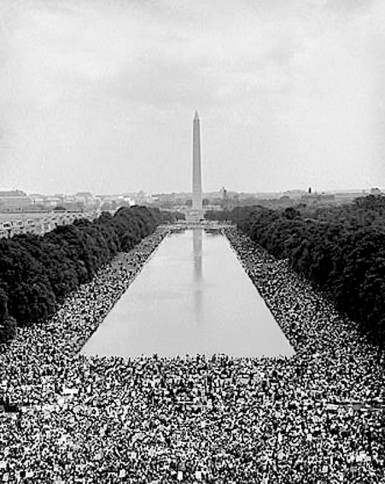

Title VIII (the “Federal Fair Housing Act”) of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, signed by President Johnson a week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., advanced the struggle for integration taking place in Cleveland’s eastern suburbs and elsewhere across the nation.

Title VIII (the “Federal Fair Housing Act”) of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, signed by President Johnson a week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., advanced the struggle for integration taking place in Cleveland’s eastern suburbs and elsewhere across the nation. The March on Washington, August 28, 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. called upon the nation to make good on democracy’s promise of social and economic freedom for all citizens

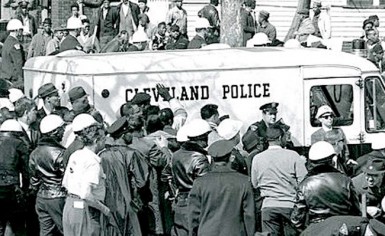

The March on Washington, August 28, 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. called upon the nation to make good on democracy’s promise of social and economic freedom for all citizens  In 1967, this Cleveland Heights home, owned by an African American, was bombed in a senseless and vain attempt to halt the suburb’s integration.

In 1967, this Cleveland Heights home, owned by an African American, was bombed in a senseless and vain attempt to halt the suburb’s integration. Dr. King speaking in Rockefeller Park on a visit to Cleveland in 1967. The previous year he had dramatized the issue of housing discrimination by moving his family into a grimy apartment on the segregated west side of Chicago and joining in protest marches into that city’s all-white neighborhoods.

Dr. King speaking in Rockefeller Park on a visit to Cleveland in 1967. The previous year he had dramatized the issue of housing discrimination by moving his family into a grimy apartment on the segregated west side of Chicago and joining in protest marches into that city’s all-white neighborhoods.The Cleveland Foundation began to address the issue of housing segregation in the early 1960s, making grants to support the Ludlow and Moreland neighborhood associations that sprang up to encourage the integration of neighborhoods straddling the boundaries of Cleveland and the inner-ring eastern suburb of Shaker Heights. Thus began the foundation’s longstanding commitment to promoting fair housing and integration.

In 1960, only one of every 40 minority families in Cuyahoga County lived outside the City of Cleveland. Most people accepted the status quo. It required courage on the foundation’s part to lend moral and financial support to a wide range of groups working to overturn entrenched patterns of housing segregation. In addition to neighborhood associations, grantees included the Fair Housing Council, which successfully lobbied municipalities across the county to pass fair housing resolutions in the mid-1960s, and the Heights Community Congress (HCC), a broad-based coalition of organizations and individuals that monitored the progress of integration in the inner-ring eastern suburb of Cleveland Heights. When warranted, HCC took remedial action to maintain racial balance and harmony, filing lawsuits against local realtors, for example, that set standards for nondiscriminatory treatment of African-American home buyers.

Cleveland also participated in Operation Equality, a Ford Foundation demonstration project to improve minority housing opportunities in eight test cities. The willingness of the Cleveland Foundation and its affiliated Greater Cleveland Associated Foundation to match a Ford grant of $180,000 allowed Operation Equality to open four field offices in Cleveland in 1966–67. Field workers provided assistance to African-American families willing to risk buying homes in white neighborhoods. Having helped to relocate 200 African-American households during its first two years, Operation Equality-Cleveland decided to shift its focus from providing services to individual clients to attempting to bring the real estate industry into compliance with federal fair housing provisions passed as part of the 1968 Civil Rights Acts. The Cleveland office joined with the U.S. Department of Justice to file fair housing suits against several area apartment management firms in the early 1970s that resulted in consent agreements governing more than 10,000 units.

Progress toward integrating the city’s eastern suburbs became noticeable. By 1970, one of eight African-American households lived outside Cleveland’s boundaries. As outward migration continued, Shaker Heights, Cleveland Heights and University Heights were faced with the prospect of resegregation—that is, they were well on their way to making the transition from all-white to all-minority. Rather than ignoring these demographic trends, municipal and public school officials formed the East Suburban Council for Open Communities (ESCOC) in 1983 with the support of the Cleveland Foundation.

ESCOC offered low-interest loans from special-purpose funds established in Shaker and Cleveland Heights to home buyers willing to settle in neighborhoods where their race was underrepresented. In 1988, the integration maintenance program received an Innovations in State and Local Government Award, one of 10 presented by the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University that year. Funded by the Ford Foundation, the award recognized ESCOC as the “nation’s first public-private inter-jurisdictional approach to integration, targeting affirmative marketing to all home seekers on a sub-regional rather than local basis.” Equally important, the organization had helped to slow resegregation in the Heights and maintain the racial diversity that is a prized attribute of the area today.

1961

A Central Planning Agency for University Circle

A 1957 master plan for University Circle identified the immense land-use challenges facing Cleveland’s civic mecca, then home to 34 education, arts and culture and healthcare institutions. Affirming the importance of maintaining the Circle’s viability, the Cleveland Foundation made a three-year grant of $180,000 in 1961 to support the operation of the University Circle Development Foundation (UCDF), a central planning agency whose establishment had been recommended by the master planners as essential to the Circle’s orderly growth.